In the house I grew up in, our attic was stacked with boxes. A decade could be retraced in an hour’s time. Births, deaths, baptisms, confirmations and graduations and various ephemera littered the rafters. Frayed boxes bulged with old photographs and letters.

I was the youngest of my family and almost the youngest of my entire extended family. So much had transpired before I had attained an awareness of what was going on. In the attic, I was able to look back and recapture some sense of my family’s life before I came along. I found it captivating to think about where they had lived and to read about the details of their lives. And rich material there was.

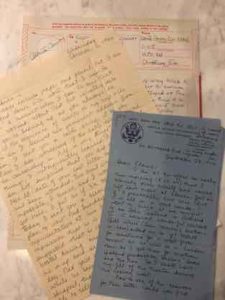

First, there was a set of letters written by my great grandparents in the years around 1901. Another set from around 1915-1927 had been written by my grandparents to each other. In addition, Mom had saved her diary from 1932 as well as her letters home from when she was a college exchange student in Paris in 1937-1938. Then there were the letters written home by my mother in 1944 and 1945 when she lived in London and Paris and worked for the Office of War Information. And for good measure, her 1944-1949 date books were thrown in the same box.

Dad, too, had saved all his war letters and datebooks as well. An oil painting of my Army uniformed Dad was displayed next to the hanging bags on the rafters in the attic. There was something about the painting that neither he, nor my mother, could look at on a daily basis. The painting has those eyes that never leave your gaze, no matter where you are standing. It stayed in the attic until they moved out of my childhood home in 1999 and then it only saw the light of day when we dragged it out for his funeral in 2004. I think one of my sister’s has it now – and I know it looks great in storage.

All these years later, I have decided it is time to lay down on paper the experiences my mother had up and until 1945 when she returned from Paris after nearly twenty one months of overseas work. My children have an idea of their grandmother but their memories of her in the good years, before her mind was befuddled by dementia, are less than robust. And they certainly have no clue about what she did during the war.

Mom’s wartime job was one of government work, but in the run-up to and in the aftermath of D-Day, Londoners, and everyone at OWI, began to see the end of the war in sight. While they were very aware of the immense human sacrifice that our soldiers made, it was a relief to think the war would end. The whole psychology was different.